- Home

- Matthew Berry

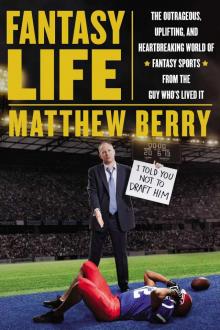

Fantasy Life: The Outrageous, Uplifting, and Heartbreaking World of Fantasy Sports from the Guy Who's Lived It Page 2

Fantasy Life: The Outrageous, Uplifting, and Heartbreaking World of Fantasy Sports from the Guy Who's Lived It Read online

Page 2

ME: What?

HER: What what?

ME: You’re staring at me.

HER (genuine curiosity): I’m trying to see your horns.

ME: Horns?

HER: My dad said all Jewish people have them.

Half the table nodded. True story. Welcome to Texas, Berry.

So as a bit of an outcast, perhaps it was only natural that I would be drawn to a brand-new, niche game like fantasy baseball and that I was so willing to try something, anything . . . as long as it included me.

It was early spring in 1985, and I was actually a high school tennis player. Yes, that’s right. In football-loving Texas, I played tennis, a sport you play without teammates. Looking back, it’s amazing I had any friends at all.

I took tennis seriously. Won some tournaments, ranked as a USTA junior in the state of Texas, went to the state finals in high school, etc. This is only important to our tale for this lone fact:

As a result of being good at tennis, I took private tennis lessons. And that’s only important because of the guy I took them from, the local tennis club pro, a man named Tommy V. Connell. Or as I prefer to call him, owner and general manager of the always plucky TV Sets.

I was walking up to see him for my lesson one day, and he was talking to his best friend, a guy I would later come to know as Beloved Commissioner for Life Don Smith, owner of the Smith Ereens. They were talking in a strange language that felt newly familiar, and going through names of guys they could ask “to join.” What they were discussing would set my life on a course I’d never imagined.

“Are you guys talking about Rotisserie League Baseball?”

They were just as shocked that I knew what they were talking about as I was that anyone besides me read Rotisserie League Baseball, a weird little green book that had just been released detailing the rules, spirit, and advice about how to play “The Greatest Game for Baseball Fans Since Baseball.”

Don, Tommy, and their friends were forming a league, and they needed a 10th guy who had both heard of this weird thing and was willing to try it. It was to be a National League–only fantasy baseball league. They would have to do stats by hand because in 1985 there was no Internet, no one had cell phones, and people still bought magazines for their porn.

I was 14 years old.

The other guys in the league were in their twenties and thirties, and I was a freshman in high school. But we’ve all been in leagues where you just need one more guy—any guy—to play, and that first year the Fat Dog Rotisserie League was no exception.

I joined because it seemed like a helluva lot of fun.

Almost 30 years later, I can confirm it is, in fact, ONE HELL. OF A LOT. OF FUN.

Fifteen years after my initial fantasy auction (blurrily pictured here), I would get my first job writing about fantasy sports. Four and a half years after that, I would start TalentedMrRoto.com, and in 2006, just a scant 22 years after this picture was taken, I sold the site and came to ESPN as its senior director of fantasy sports.

Along the way, a bunch of things happened. There were wars and presidents, and apparently some big wall overseas fell at some point, but probably most important, fantasy sports became not just mainstream but a way of life.

Fantasy sports are popular for lots of reasons. The competition with your friends, family, and even strangers. The rooting interest it gives us in sporting events we would normally never care about or the athletes we never dreamed of cheering for. The ease of it, thanks to the Internet and other technology.

But more than anything, it’s fun.

For many people—and I’m in this group—it’s all about your league. The guys and gals who are your league-mates. The good times, the bad times, the highs and the lows, it all comes back to someone’s league. A bad league ruins the experience for so many, which is why I was so lucky that the Fat Dogs, my original league, is such a great one.

It’s where I learned not only how to play but how to play the right way, to enjoy the game with a good group of guys who want to win, sure, but who mainly just want to laugh and have fun.

We draft on the same days every year. (Traditions are crucial for any good league.) The Friday after opening day we do the Lone Star American League auction (started the year after the Fat Dogs). Then on Saturday we do the National League. We sit in order of last year’s standings, with the champion at the head of the table, second place sitting to his right, third next to second, and so forth.

Twelfth place gets to throw the first guy out for auction, and the pizza is delivered promptly at 12:30. Even though I live in Connecticut now, I fly back to College Station every year. That’s right—the league still exists.

In fact, get this: 6 of the original 10 guys from 1985 are, many, many years later, still in the Fat Dog League. And two others have been in it for 20-plus years. For all the amazing advances the Internet has made to help the growth, popularity, and ease of fantasy sports, I see one major downside. That folks no longer have to be in the same room to draft. It’s just not the same.

Especially when you get to draft with people you’ve known for more than a quarter-century. Because when you do something embarrassing at the draft—and we all have over the years—it gets remembered. Forever. And the amount of trash talk is both hilarious and awe-inspiring.

To this day, fellow Fat Dogger Woody Thompson, owner of the Thompson Twins, is reminded of the year he tried to draft promising youngster Ryan Howard to his minor league team, only to be told Howard was already owned. By him.

When we started, we didn’t draft with personal computers because they didn’t exist. Standings came once a week . . . by mail.

As for transactions, well, let Beloved Former Commissioner for Life Don Smith tell you.

“Originally, if someone wanted a player, they just called the commissioner. First to get to me, first served. Anyway, one Monday during that first year I was sitting in my office, and I heard a commotion. My brother Terry, owner of Smitty’s Grills, was running down the hall with his five-year-old daughter in tow. ‘C’mon, Heather, hurry, we’ve got to see Uncle Don! Hurry!’ There were no cell phones, of course; it was about 8:30 AM, and he was taking her to school, but he’d heard on the radio that San Diego had a new starting outfielder. He was huffing and puffing, dragging his kid into my office. ‘I claim Carmelo Martinez!’ he wheezed as his confused daughter looked at her out-of-breath father. The Grills got their outfielder but Heather didn’t make it to school on time. And we enjoyed the craziness of that moment for the next 26 years.”

Yeah, we did, Don, and it was with great sadness to all the Fat Dogs when Terry passed away in March of 2011. I’ll never forget Terry dragging his young daughter down the hall.

You know, since that first year, I’ve lost my glasses and a good chunk of the hair, I’ve gained experience, perspective, and weight, but most important, I have played in hundreds of fantasy leagues covering all kinds of sports and entertainment. I’m pretty sure I even played fantasy hockey once. What can I say? I was young and experimental.

But the best league I’ve ever played in is still the first one. As a league, we’ve been through marriages and births, heart attacks and deaths, and a three-week email war over who owned Manny Ramirez. They are great guys, they are pains in the ass, and I wouldn’t trade my sense of community with them for the world. Recently, in a public study, ESPN found that the average sports fan spends more than six hours a week with ESPN on one of our many platforms—TV, radio, dot-com, the magazine, our mobile apps, etc.

But the average fantasy player?

He or she spends over 18 hours a week with ESPN. Almost a full day a week!

Oh yeah, people are into it. But while stats like that are impressive and speak to the broad appeal of fantasy, the truth is it’s all about the people. It’s not the draft, it’s not the trash talk or the punishments, it’s not even the winning (okay, maybe

it’s a little bit the winning). It’s the people. It’s the people who make the draft and the trash talk and the punishments and the winning what it is.

Consider the story of Kevin Hanzlik from Northfield, Minnesota. His team, Hanzie’s Heroes, lost in the finals of his 2011 10-team fantasy football league. It happens. The fact that he lost to his 87-year-old mother, Pat Hanzlik? Not as common. Grandma Pat, as she is known, rode Cam Newton’s rookie year and 16 touchdowns from Calvin Johnson to a title for G-Ma’s Marauders.

Look at that picture. Come on. She’s 87 years old. Get better than that.

Because of fantasy sports, I’ve had amazing experiences that I would have never thought possible. And I’m not alone. What follows are stories about me, stories about players, and stories about, to paraphrase Daniel Okrent and the founding fathers, “the greatest game for sports fans since sports.”

So whether you are a lifelong fanatic, have never played before and want to understand what the fuss is about, or just have an afternoon to kill and need something with a bunch of small, easy-to-understand words, you’ll soon realize what everyone else does.

Fantasy sports is outrageous, poignant, obsessive, heartwarming, heartbreaking, frustrating, crazy, uplifting, life-changing, monstrously fun, very addicting, and, quite simply, the best thing ever invented.

You’ll see.

TIME-OUT:

Lessons of the Fat Dogs

The key to a great fantasy experience is a great league. And the lessons of the Fat Dogs are as good a blueprint as I’ve found in 30 years of playing:

We play fair: We all want to win, but we also play for fun. A victory you had to cheat to get isn’t a real one. And as you’ll see in upcoming chapters, people will do insane things to try and win a league. However, a league where no one cheats is a happy league. With the Fat Dogs, only one person has to report a trade. Every other league I’ve played in has to have both teams confirm. When I asked Beloved Commissioner for Life Don Smith about this early on, he said, very simply, “Well, if you’re lying about the trade, we’ll all find out pretty quickly.” We’ve never had a problem.

Now THAT’s a trade deadline: Our trading deadline is the final out of the All-Star Game. Every year a bunch of the owners gather to watch the game, and those of us who can’t make it call in knowing that everyone who needs to trade will be checking in. Trade talk really heats up around the eighth inning, and nobody wants a one-two-three ninth. Of course, technically, the trade deadline in 2002 still hasn’t passed. What are you gonna do? It’s a double-edged sword. Bottom line, make sure you have a trade deadline party, whether it’s the last minute of the Monday Night Football Game or the All-Star Game or even just midnight on a specific Saturday night. The league that trades together is a league I wanna play in.

Have characters: Not character. Characters. That’s a rule from Rick Hill, owner of the Zydeco Jukers. He brings a voodoo hand on a stick, Mardi Gras beads, and an iPod and large speaker to every draft. And every year, when the Jukers roster a player, loud Zydeco music blares as Rick waves the hand and shakes the beads. I’ve seen it for 30 years. It never gets old. Seriously. All leagues need silly and fun. Bring out your inner Juker.

No one tanks: Nothing—and I mean nothing—drives me more nuts than someone who stops playing or paying attention once their team is out of it. It’s not only the wrong thing to do, it’s bad karma. Even if you’re out of it, your play has a bearing on the outcome of the league for others. And next year, when you’re in the title hunt, you’ll appreciate everyone else playing the season out and keeping your opponents honest. You’re not always gonna win, but you’ll always have your fantasy pride.

Of course, the Fat Dogs don’t just rely on karma. We’re a keeper league, so after the auction we do a minor league draft, where every year at least one Ryan Howard joke about Woody will be told. And first pick belongs not to the last-place team but rather the team finishing sixth, or just out of the money. So even if it’s not your year, you still compete to try and finish sixth. It’s no unicorn tattoo, but it works for us.

A league that eats together stays together: Just like the founding fathers did at La Rotisserie Française, our league eats lunch together every Thursday, rain or shine, at Jose’s Mexican Restaurant in Bryan, Texas. During the second half of the season, this is also where we have a once-a-week, blind, free agent acquisition budget (FAAB) bidding on available free agents. If I am visiting my folks for a weekend, I will try to come in on Wednesday night, just so I can make Thursday lunch. Lotta laughs, trade talk, and studying of the standings.

Your league’s traditions can be simple or, as you’ll soon see, wildly elaborate. What they are isn’t important. The important part is that they exist at all . . .

2.

Great Rules and Traditions

or

Every Team Has to Be Named After a Weird Kid from High School

For the Dartmouth Rotisserie Baseball League, the draft that year was perfectly normal. And the drinking was very typical. In fact, everything that happened that weekend was exactly as expected. Everything, that is, except one small thing . . .

Founded by 10 Dartmouth graduates in the late nineties, the league travels to different cities every year for their draft and parties all weekend. Mike Fleger explains that the “winner of the DRBL gets to choose the city. We’ve drafted in Las Vegas, South Beach, New York, Boston, Washington, DC, Chicago, Key West, and even Columbus, Ohio.”

Draft weekend actually starts when they get to town on Wednesday night, and they go strong until they leave on Sunday. “The group of guys all live up to the tradition of ‘Dartmouth boys’—hard-drinking, partying guys’ guys,” Mike says.

And so, with the draft done, Mike and the gang went to a bar and, following the natural progression of life, did what guys do at bars. “A guy in the league was hitting on a girl, and someone took a photo of the two of them. In the picture, they are grinning ear to ear as if they each won the one-night-stand lottery.”

After the picture, the rest of the league went back to drinking and left their buddy to hang out with his new friend. And everyone forgot about the night.

Until the next year’s draft.

“We’ll find any reason to give a guy shit,” Mike says, “and in this case it was easy. The girl from the bar had certain features . . . masculine features.” That’s right. Their drunk buddy hooked up with a dude. So what does the league do? Let him forget it? Of course not. They all get T-shirts made up with a picture of this guy and his “date” and wear them to the draft.

I’m guessing these shirts don’t get a lot of repeat wear. But it was a success that night. Not only did they manage to give their buddy tons of grief, but it ended up becoming a great opening line to girls afterward. “How many men do you see in this picture?” Mike and his buddies would ask as they approached. “Fifty to 60 percent responded, ‘Two.’”

I’ve seen a close-up of the photo, and I assure you, gentle reader, 40 percent of the women that night were wrong. It is definitely two guys in the picture. And just to be clear, I have no issue with someone hooking up with a dude if a dude is who you want to hook up with. Love who you want. But if you think you’re hooking up with a woman . . .

I told you last chapter . . . you do something embarrassing in a fantasy league and it gets remembered. Forever. At least it does in good fantasy leagues. And the DRBL is a great league. I love that they all travel to a different city to draft together every year. I love that they took the picture, all got T-shirts with it, and then waited a year to wear them. All for the sole purpose of giving one guy in the league crap.

But mostly, I love that they are all great friends from college who use this league as a way to keep in touch.

Because I can relate. Not only do I fly back to College Station for my original fantasy baseball league every year, I am still, more than 20 years later, in my original fantasy football league,

which I joined when I was in college.

Half of my high school graduating class stayed local and enrolled at Texas A&M University. The other half headed to Austin, where they attended the University of Texas. Neither was an option for me. My parents wouldn’t allow it.

Dad, or as he’s known to the rest of you, Dr. Leonard L. Berry, grew up in Fresno, California. My mom Nancy was from Long Island. Dad went to the University of Denver, Mom went to CU in Boulder, and that’s where they met. “You need to learn to be on your own,” my folks told me when it was time to start applying. “There will be times when things get tough in college and you shouldn’t be able to just drive home, do your laundry, and escape it. You need to be on your own and learn to figure it out for yourself.”

And so it was settled. They were forcing me to go out of state. And thank goodness they did. So because they had a good communications program, I chose Syracuse University. Go Orange!

When I went to Syracuse, I was like a fish taken out of its bowl and dropped into the sea. It’s like . . . Whoa! There are others like me? Who knew? Unlike small-town Texas, Syracuse had tons of Jewish kids, and I finally realized there was a genetic reason I was neurotic and talked with my hands.

I dove into everything I could there. Being a morning DJ at the student radio station? Done. Writing a humor column for the student newspaper? You bet. And most important—producing a show at the student TV station. Not just any show, but a sitcom.

Producing a sitcom is hard enough, but it’s almost impossible on university TV. There weren’t a lot of resources or equipment in 1988 when I was a freshman. Most of the TV shows they did at that time were what I called “one camera, one host, one plant.” Literally, they were all music video shows or sports highlight shows. One person would sit next to one potted plant and talk into one camera about the new R.E.M. album for about fifteen seconds. And then play a Midnight Oil video. When I told the kids running the student station that I wanted to shoot a living, breathing, fully scripted, three-camera sitcom, shot in their studio, which was no bigger than a walk-in closet, they told me I was nuts. Plus, it’s college: kids don’t want to work that hard; they want to drink and party. They said I’d never get enough help with all the things a show needs—scripts, costumes, props, a crew, you name it. “How about doing a video countdown show?” they suggested.

Fantasy Life: The Outrageous, Uplifting, and Heartbreaking World of Fantasy Sports from the Guy Who's Lived It

Fantasy Life: The Outrageous, Uplifting, and Heartbreaking World of Fantasy Sports from the Guy Who's Lived It